This blog post has been brewing for a while now. I first started mind-mapping

it about a month ago. I was going to call this “Considerate Slack Use” but this

is how I use Slack and in no way a request that you do the same as me.

If you do happen to find anything useful or adopt anything from this post, I’d

love to hear from you.

Let’s start at the beginning. Slack is a team communication tool that can be

used for collaboration. I sent my first Slack message in March 2014 and since

then it has all but replaced email for internal communication for us at work. Of

course this means that there is yet another organisation with responsibility for

our information! Slack has been an important tool over the past couple of years

for keeping connected with our colleagues while we couldn’t be together, and for

that I am grateful.

This post was partially prompted by me joining two new workspaces in the last

month. I am currently signed into eight workspaces across different devices,

with some workspaces having well over a thousand members. That’s about as many

as I am willing to join. I am not signed into all eight on any device.

I have been thinking a lot about Stolen Focus in the last few months and this

is also why I am not logged into all of the workspaces on all of the devices. I

have deactivated accounts in three workspaces to compensate for the two new

ones.

In praise of Slack (and other tools like it), it is a great leveller for remote

teams. Back in the office, I used to encourage my teammate from the desk

opposite me to use Slack rather than talk to me directly about work to include

the rest of the team equitably. Of course now we’re all remote, which is even

better.

While much of this article is specific to Slack, I apply many of the principles

to the other messaging services I use (e.g. Apple’s iMessage and Signal).

# Workspace settings

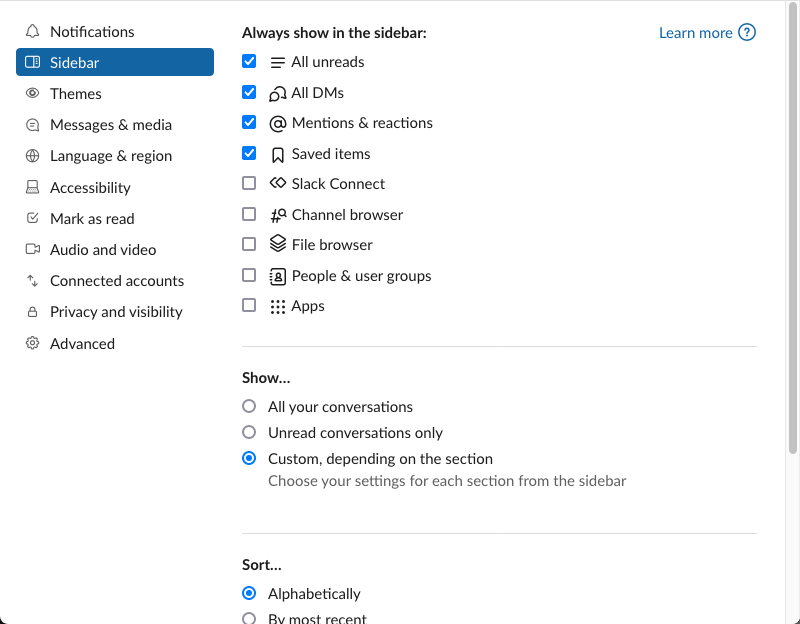

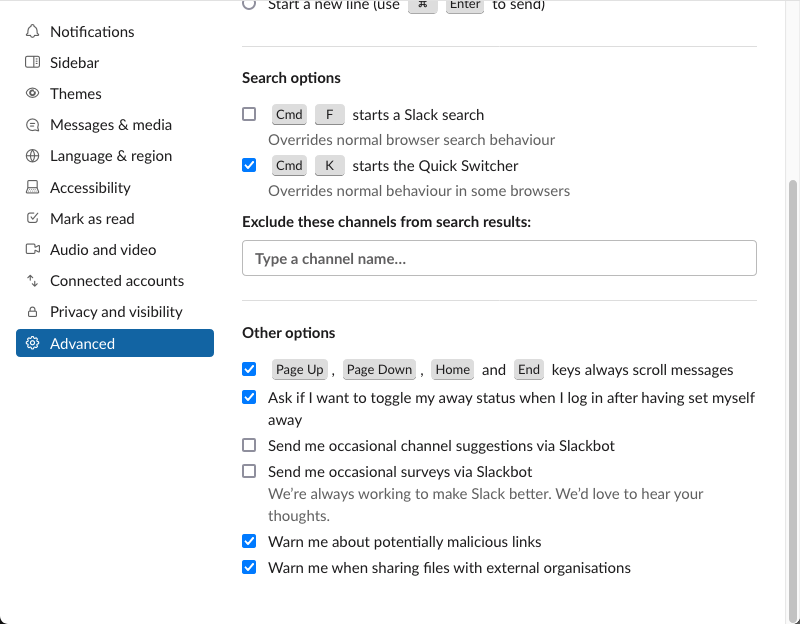

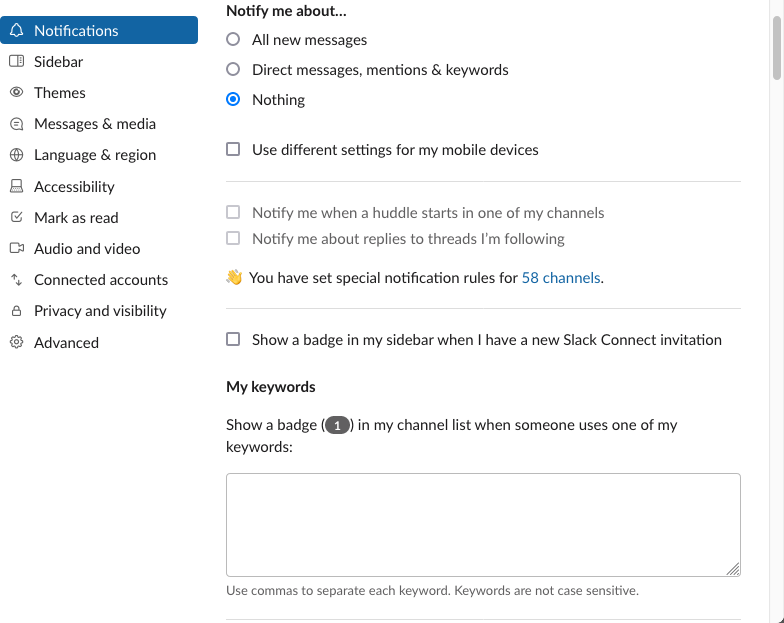

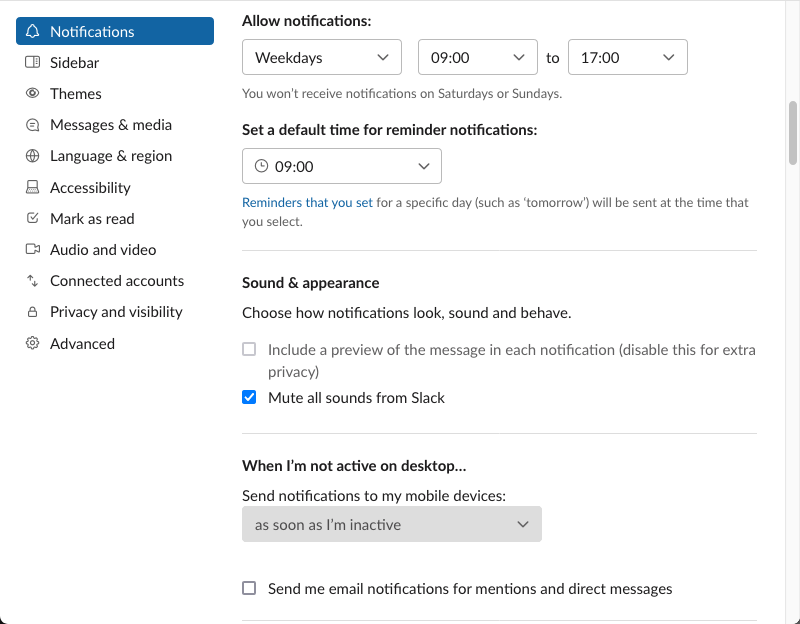

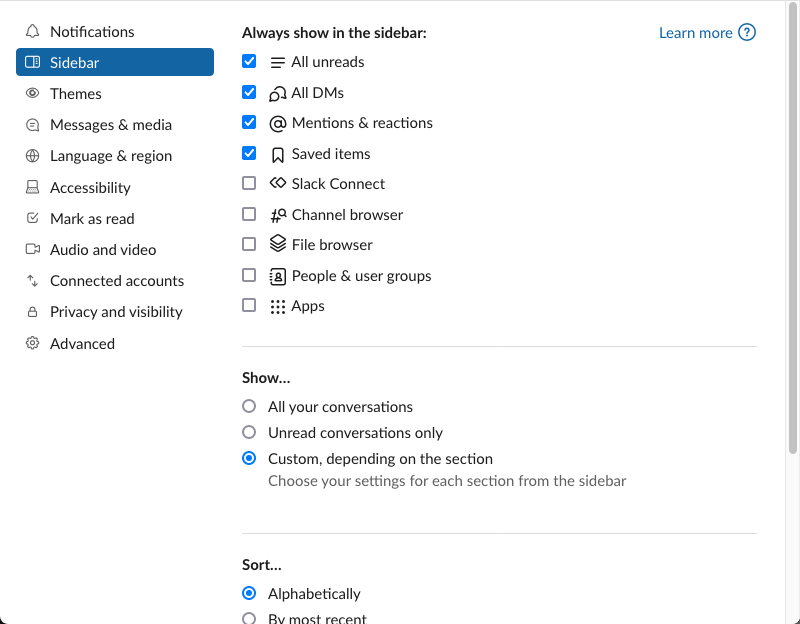

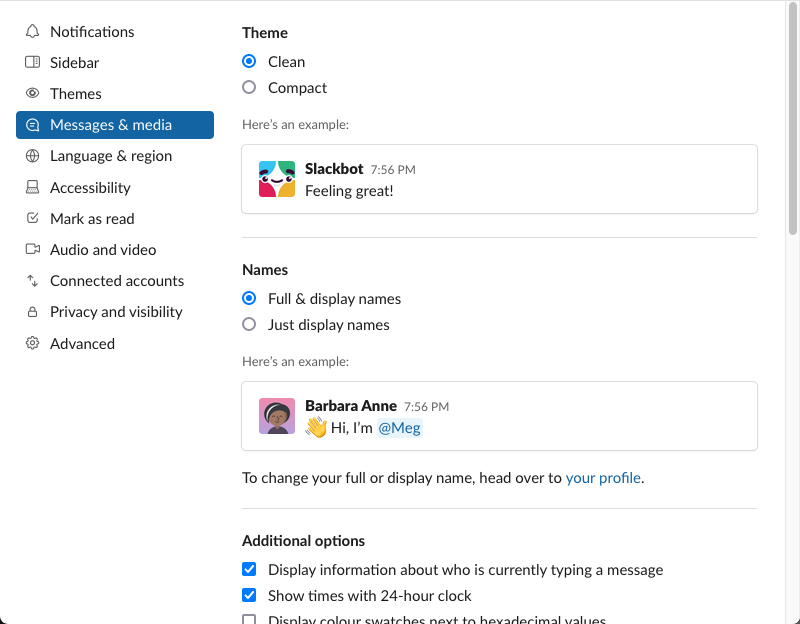

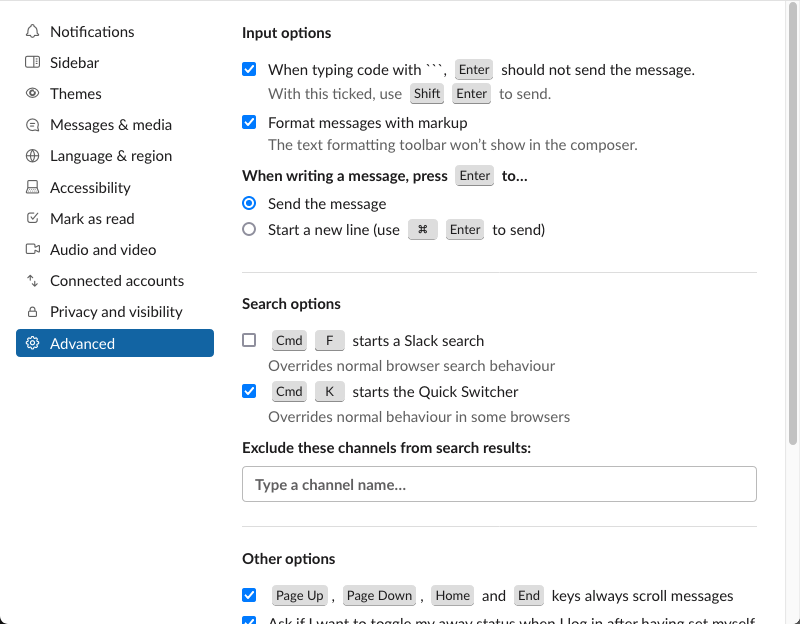

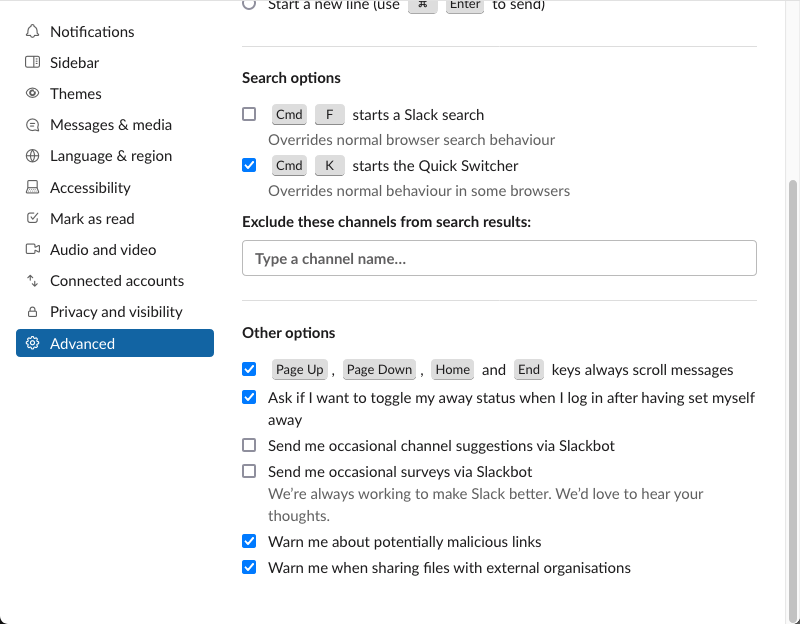

Let’s take a look at how I set up Slack. Here are some of my settings from the

desktop app.

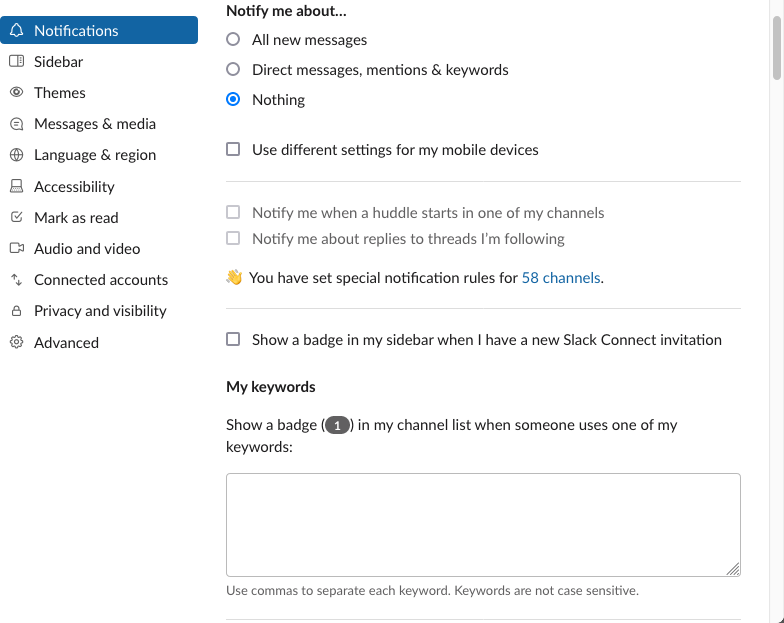

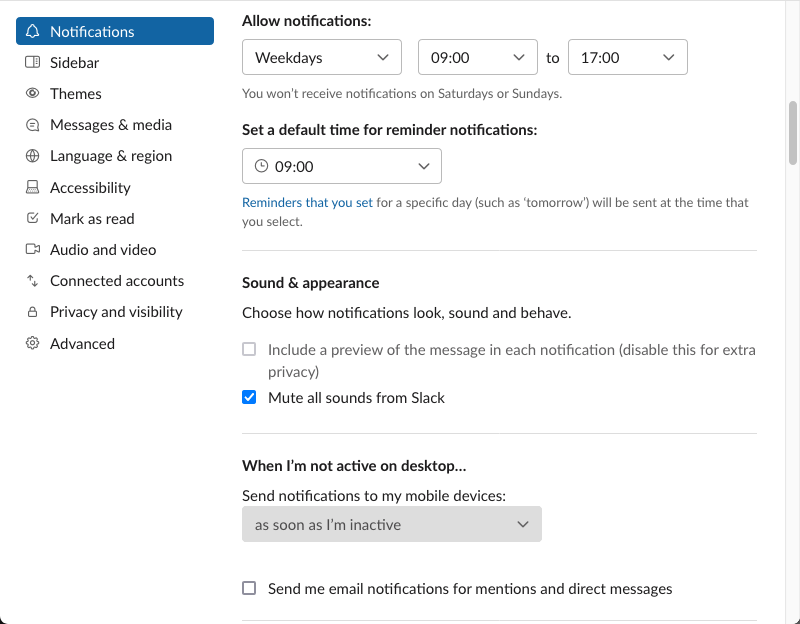

# Notifications

I turn them all off!

I read messages when it suits me, not when it suits Slack or the sender.

I minimise distractions, and give myself access to things that help me catch up.

# Themes

With much time sitting at home in during the pandemic coupled with so many Slack

workspaces, I found myself often looking for a channel to find I’m not in the

workspace I thought I was…. so I configured custom sidebar themes to make it

more obvious. I am sharing some here for you to enjoy. This seems to work only

in the web or desktop apps, not the mobile or tablet ones. Here are some of them

for you to enjoy. Simply send yourself a message with any (or all) of these sets

of hexadecimal colour values and Slack will provide you with a “Switch sidebar

theme” button in its desktop app, these propagate to mobile and tablet apps (or

at least they used to).

Work

#303030,#350d36,#303030,#85B54A,#303030,#FFFFFF,#85B54A,#85B54A,#000000,#FFFFFF

Ruby Australia

#FFFFFF,#452842,#FFFFFF,#8C5888,#FFFFFF,#F71264,#8C5888,#F71264,#F71264,#FFFFFF

The Complete Guide to Rails Performance

#052041,#350D36,#052041,#EA5E42,#052041,#FFFFFF,#EA5E42,#EA5E42,#052041,#FFFFFF

parkrun

#3E3E77,#350d36,#3E3E77,#FFA300,#3E3E77,#FFFFFF,#E21145,#FFA300,#2B223D,#FFFFFF

Solarized light

#EEE8D5,#350D36,#EEE8D5,#2AA198,#EEE8D5,#839496,#CB4B16,#CB4B16,#EEE8D5,#CB4B16

Solarized dark

#073642,#350D36,#073642,#2AA198,#073642,#839496,#CB4B16,#CB4B16,#073642,#CB4B16

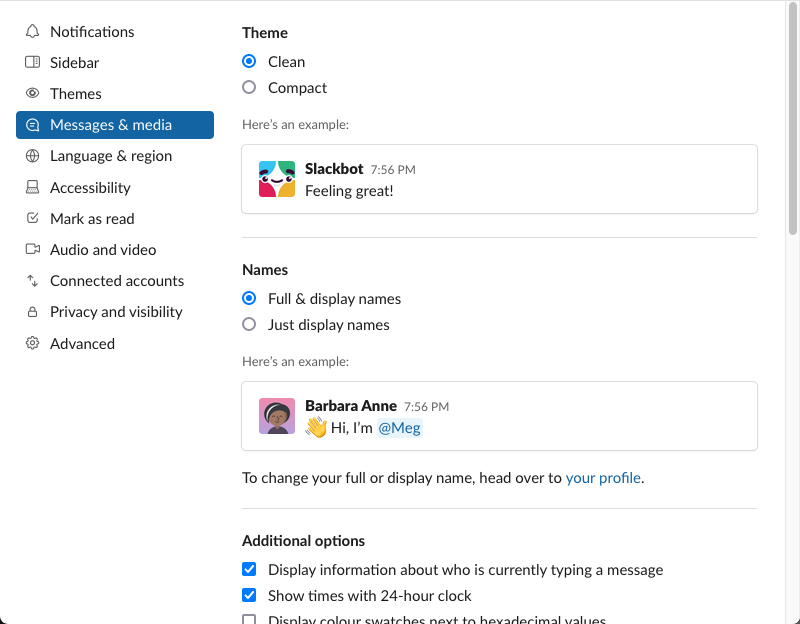

I keep these Clean and use Full Names as I like it to be obvious who I am

conversing with.

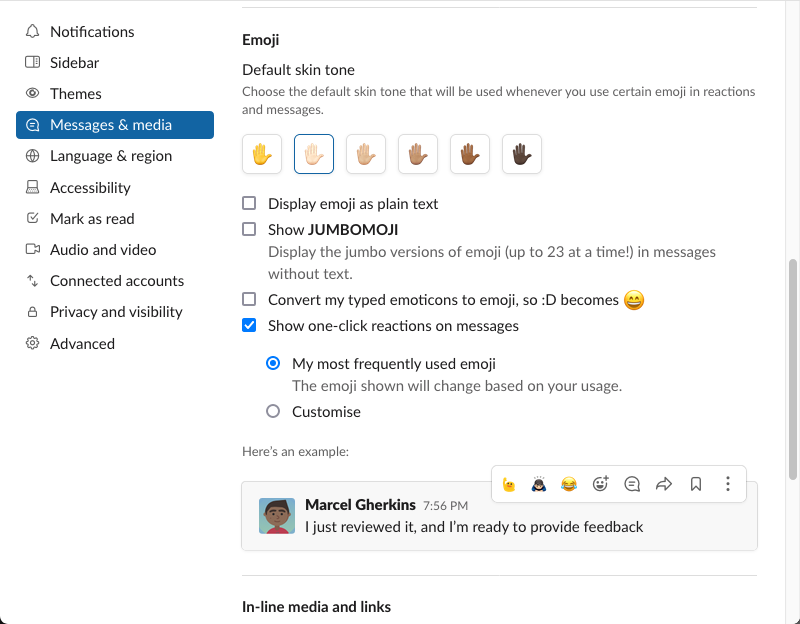

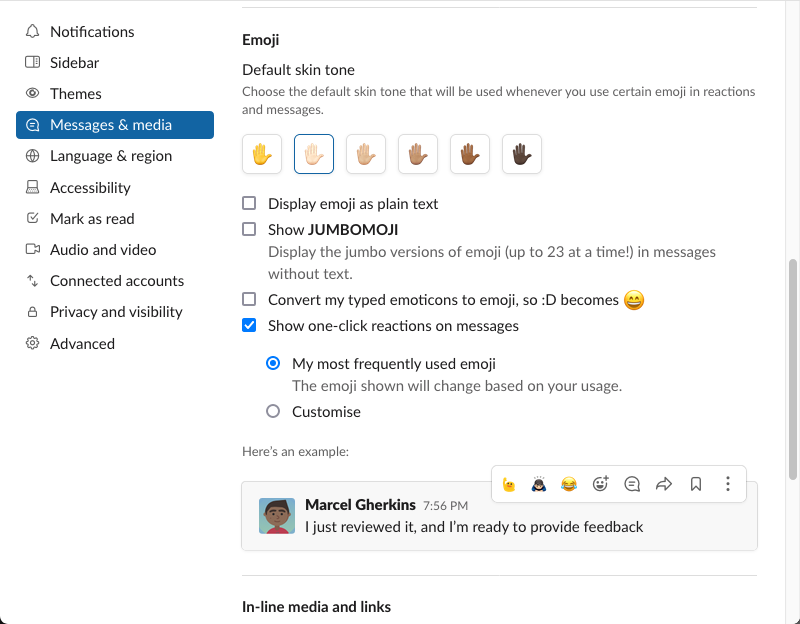

Emoji are interesting, especially when it comes to skin tone. I’ve stuck with

the default skin tone emoji since the modified ones were released but based on

an article I read recently on Which skin color emoji should you use? and

conversations with friends, I have switched to one more aligned with my own

pigmentation.

Showing one-click reactions with my most frequently used emoji on messages can

really speed up my usage.

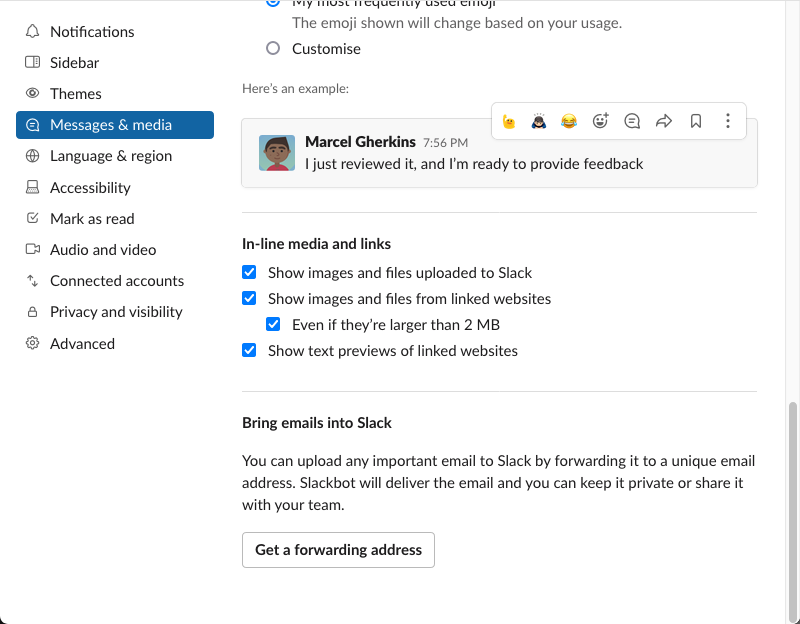

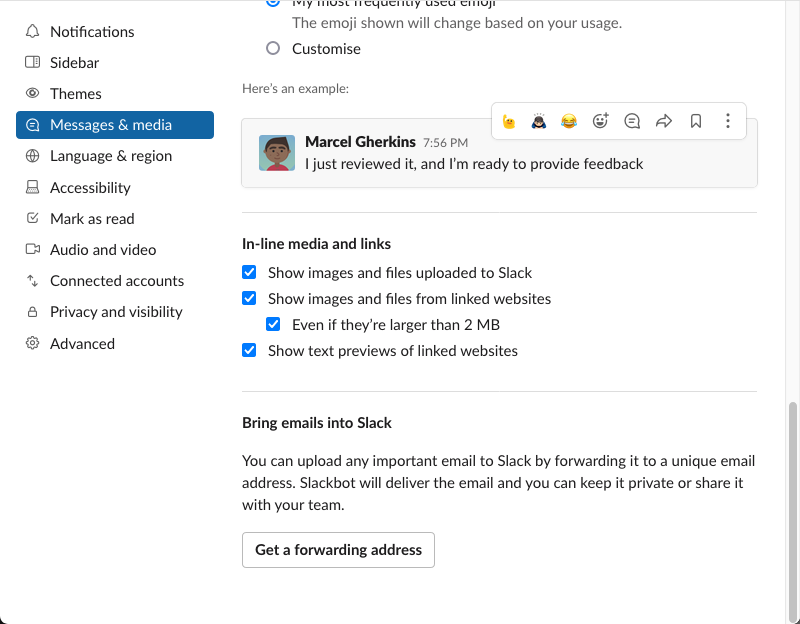

I do not bring emails into Slack (or Slack messages into email). I’ll read them

once.

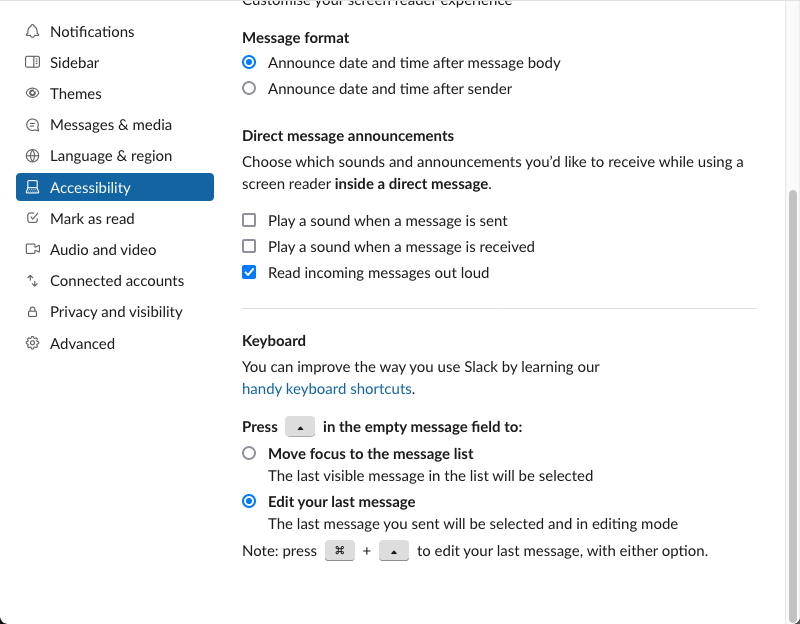

# Accessibility

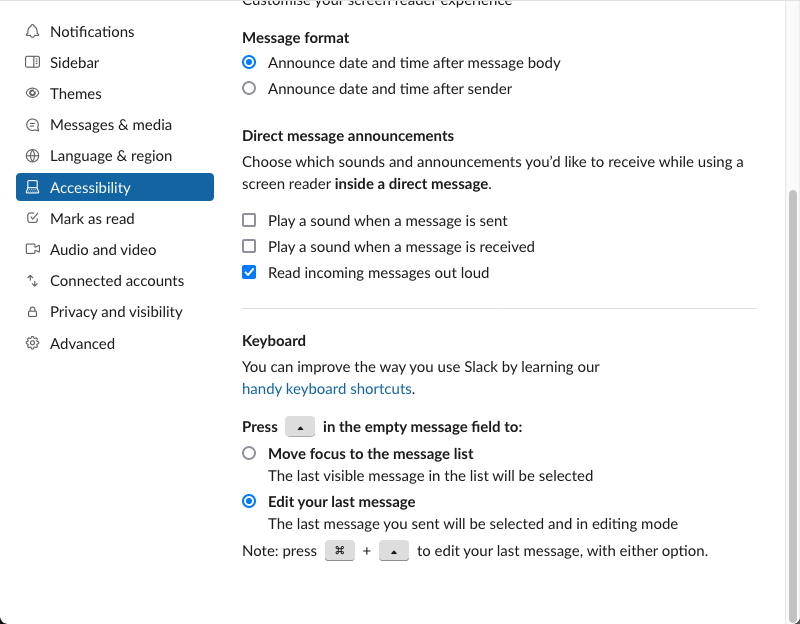

I set Accessibility settings so that the up arrow will edit last message.

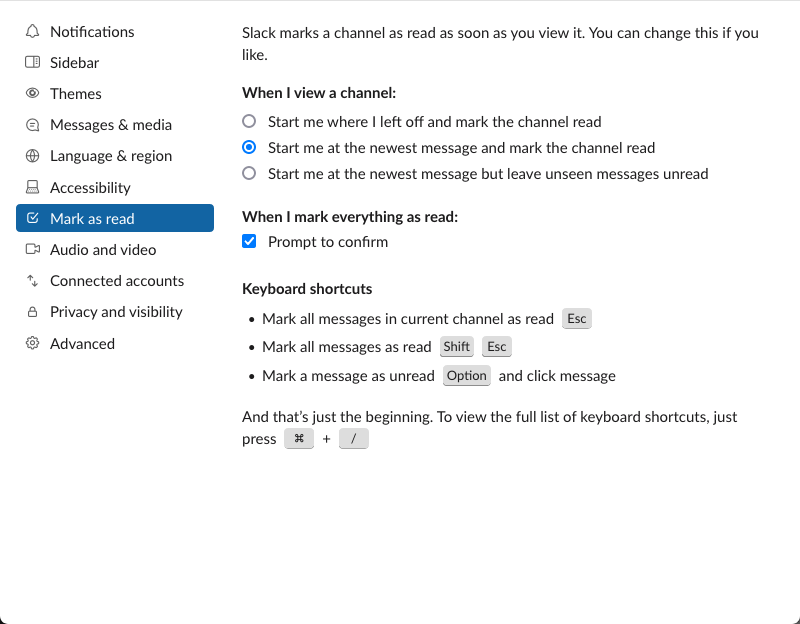

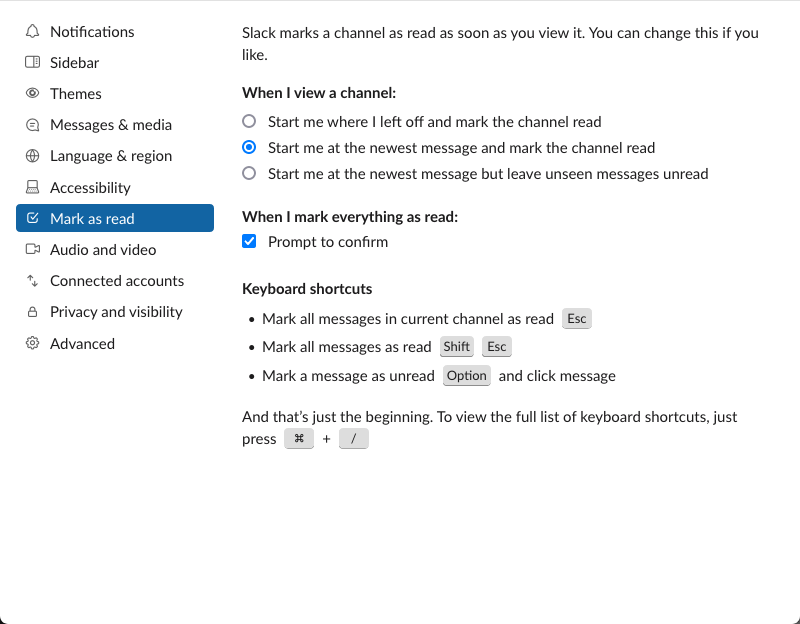

# Mark as Read

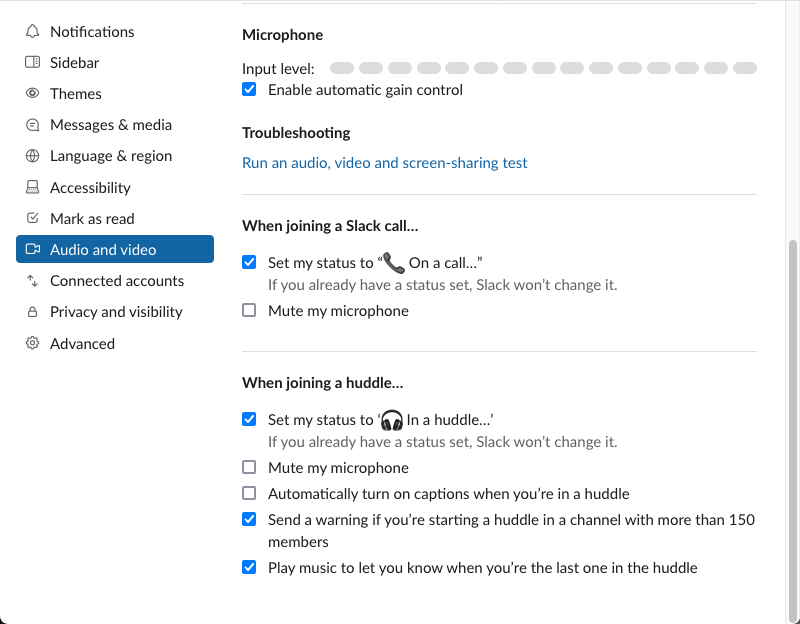

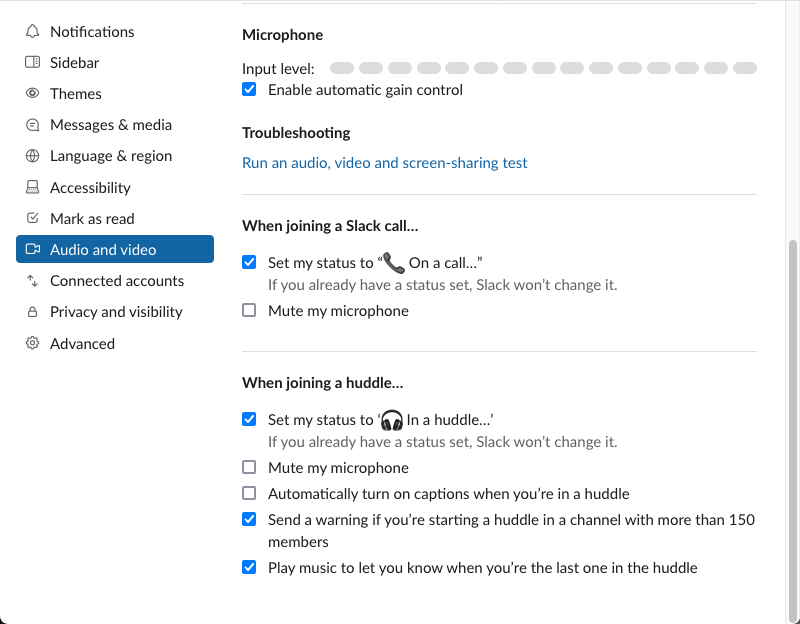

# Audio and Video

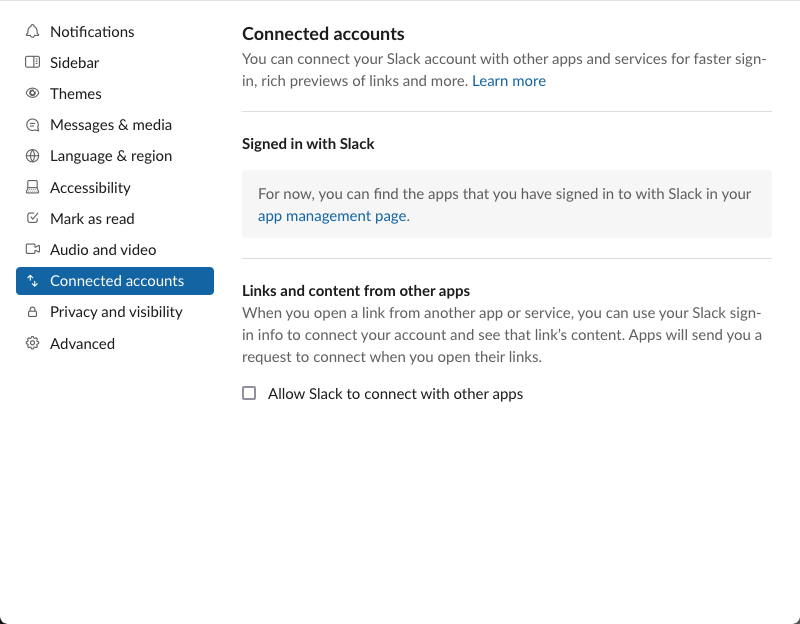

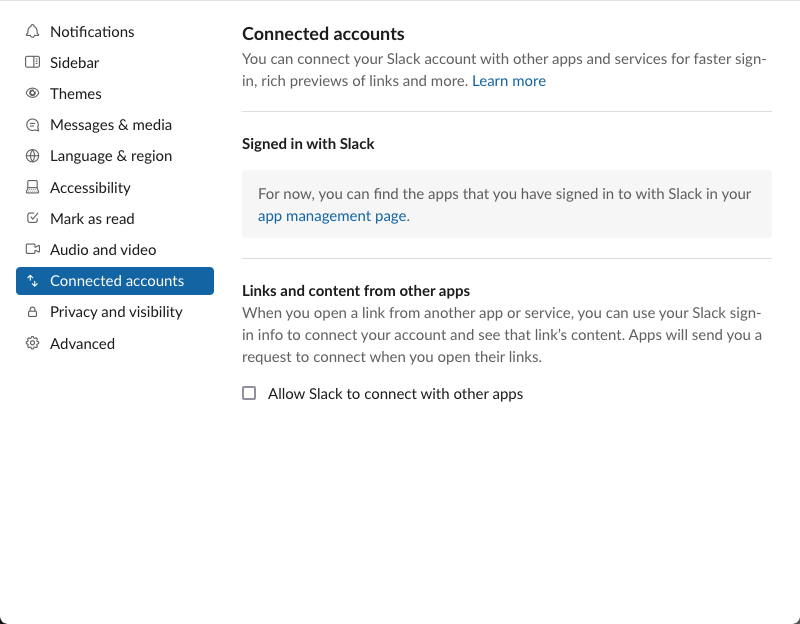

# Connected Accounts

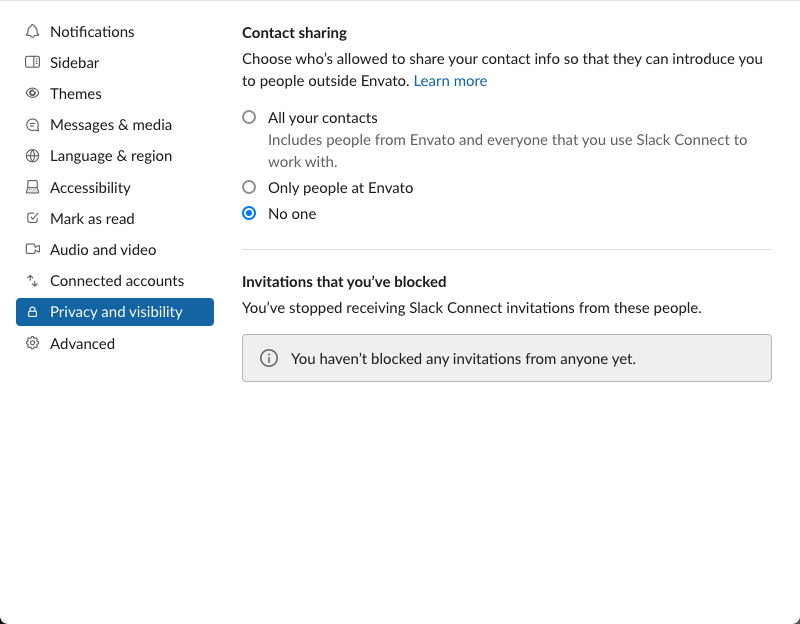

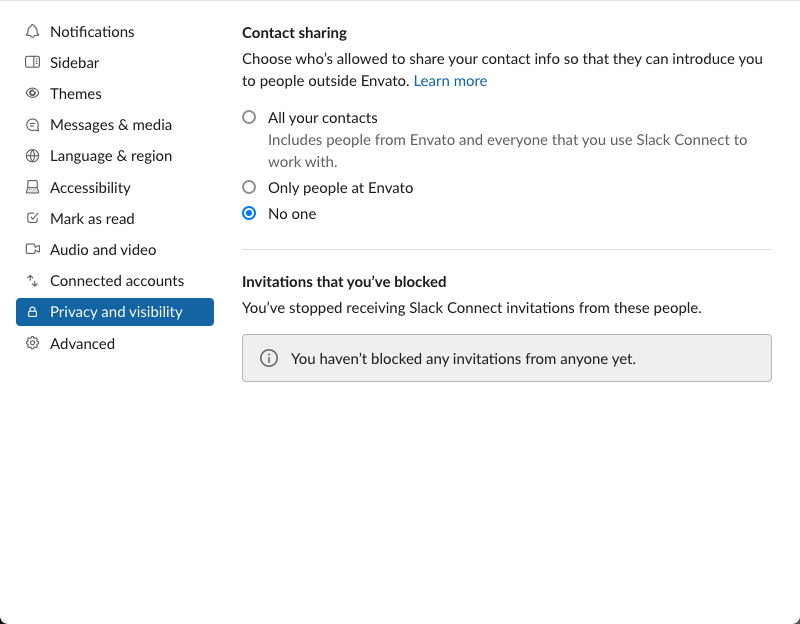

# Privacy and Visibility

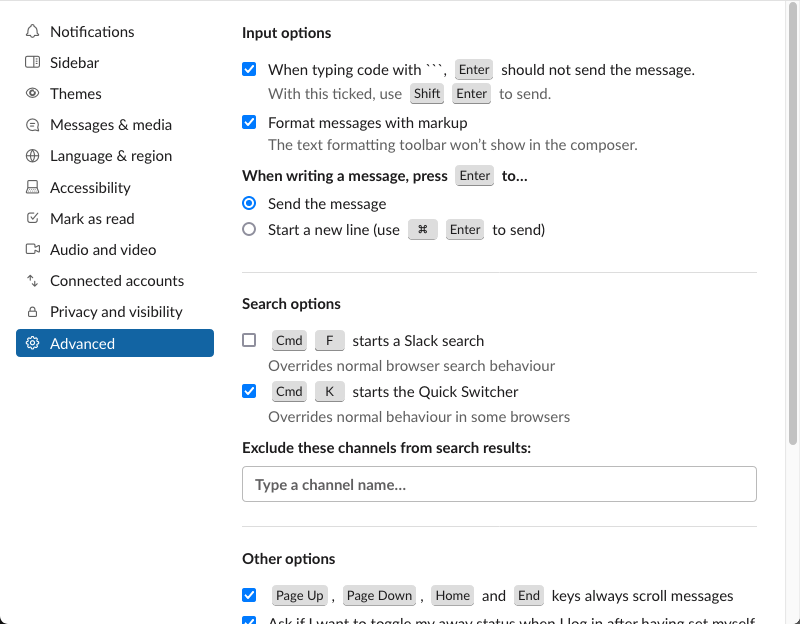

# Advanced

# Do I need access to this workspace on all devices?

A simple rule here is “No work Slack or email on my personal devices”, which I

embraced in January 2020 and have not looked back. Not even once. I have a cheap

Android phone for work, which lives on my desk except when I’m on-call. This

allows me to switch off at the end of the working day.

Equally, workspaces that are likely to distract me during the working day are

not on my work laptop. I can read these over lunch on my tablet.

# Channels

I have found establishing a pattern for when channels should be created, renamed

and archived really helps with both information organisation and personal focus.

I really value transparency in any organisation, so the first thing I’ll say

about channels is this: make channels public unless you have a really good

reason not to, such as a confidential personal matter. Public channels are

better than private channels and private channels are better than direct

messages.

As initiatives are created, I like to start a new, public, Slack channel for

interested parties to share their thoughts. This helps us get feedback early and

often as well as providing an easy to access repository of information.

Bookmarks at the top of channels help folks find the information they need. I

have come to prefer these over pinned posts because they’re more visible in the

desktop app.

Channels for teams are a good idea. For a team “foo”, I would likely create the

following channels each with meaningful descriptions:

-

🔒foo-chitchat (private), a safe space for team members to talk between themselves

- Bookmarks to video chat, working agreements and maybe a team shared playlist for fun

-

#foo-team (public), a place for the team to work transparently, allowing

others to see what’s going on and perhaps a Chatops bot

-

Bookmarks to the team’s sprint board, playbooks and shared documents

-

Use the channel topic for reserving team resources, such as staging

environments. I like to use the 🆓 emoji and personal emoji for team

members for reservations.

-

#foo-helpline (public), a place for anyone in the organisation to ask

questions of the team and get timely answers. Some answers may be automated

using Slackbot or the team’s own bot user.

- Bookmarks to the teams’s help centre articles or frequently asked questions (FAQs)

-

#foo-notifications (public), for any automated posts, so that they do not

interrupt conversations in the #foo-team channel.

- Bookmarks to any dashboards which show the current state of systems this

team cares about and the sources of any incoming notifications.

Teams evolve and team names change. This is a good point to rename the channels

with the team, this makes it easy for people to find you. Slack handles renames

well so folks should be able to find you by an old name or the current name.

Archive channels when they are no longer in use. This makes it easy for folks to

find the channels they need when they use the channel switcher, while still

being able to find the content they need in the search results.

I “star” channels for the teams I am on, they take priority when reading.

Equally, I mute those that I need to read eventually. It’s about prioritising

my time and attention. I also leave those channels that provide me with more

noise than signal, there is joy in missing out!

I have applied this to social media, too, and feel great!

# Threads

Threads can be good for completing a discussion without dragging a busy channel

along for the ride but sometimes it’s better to break these out into a new

channel. There have been recent discussions in my work channels that I’ve broken

out into new channels as threads with fifty responses are beyond manageable. A

good trigger to consider this is when choosing the “Also send to #channel”

option on a reply.

# Direct messages

Personally, I would rather use email than direct messages (DMs) but at the same

time, I adhere to the organisational norms. I do like to share URLs through DMs

during audio or video calls as these tend to persist longer than the call

itself. I’ll put a description with the URL to make it easier to find long after

the call has ended.

Speaking of email, I don’t send anyone a Slack message to let them know I’ve

sent them an email. They’ll see the email when they check their email on their

schedule. If I want to notify somebody about something urgent, that they need to

know right then, I’ll put the whole message into Slack rather than use Slack as

a layer of indirection.

I try to put all of the greetings, context and details into a single post to

reduce the number of notifications at the recipient’s end. As someone who is

both on-call and who has supported on-callers over a number of years, I know

that a flood of notifications can be a cause of anxiety so I like to keep these

to a minimum. I also don’t just say “hello”.

DMs are an information black hole where knowledge goes to die. If someone asks a

question privately and it can be answered publicly, I’ll bring the question and

the answer to a public channel because the answer is likely to help more than

the person who asked it.

It is ironic that I more often find knowledge at work by searching Slack over

searching Google Docs. Google. Docs.

Slack allows sending DMs to groups of recipients. I prefer to give these groups

a name as it gives context to the conversation and makes it easier to add and

remove members as appropriate. This also makes a good decision point: is this

conversation public or private? And then we’re back to channels.

# Emoji

I love emoji and I use them liberally. Reaction emoji are better than threads,

which are better than new messages. Again, this comes back to minimising

notifications and noise for others.

When I write a longish Slack post (the kind that could probably be an email),

I’m often left wondering who’s read it. When I read a longish Slack post (the

kind that could probably be an email), I leave a reaction emoji on it to let the

author know that it has been read.

# Messages

Some thoughts on the messages, themselves.

I include some context and sometimes a quotation from pages when I share them

them and I format quotations as quotations. I find code blocks a strange choice

for this but that approach seems commonplace. Starting a line with a greater

than sign “>” marks it as a quotation. I know that not everyone unfurls URLs and

that the resource at a given URL is subject to change or deletion and may not be

the same when the message is viewed in the future. The message should be useful

to future readers.

Speaking of on-call, I often “talk to myself” when troubleshooting an issue.

This helps me clarify my thinking and occasionally will attract help from others

who happen to be around. This approach also provides real-time updates as to how

we’re going, in case any stakeholders are lurking. These messages, screen grabs,

charts, and so forth, serve as useful, time-stamped information when conducting

post-incident reviews. I recommend this.

# Notifications

I avoid @channel and @here notifications as most Slack channels I am in span

multiple timezones. To me these alert mechanisms feel like standing on my desk

in the middle of an office and shouting at absolutely everyone. I just wouldn’t

do it.

Similarly for personal mentions, I keep my use of these to a minimum. In a

public channel, it feels like shouting at somebody across an office, when I’d

rather walk over to them or leave a note on their desk instead.

If Mel has said something previously, I say, “as Mel described above”, not “as

@mel described above”. Mel does not need to have their attention sucked back

into that conversation from wherever their focus currently is.

I generally don’t use mentions in threads or DMs as I’ve never seen the point.

It feels unnatural to address somebody by their full name or “handle” (does

anyone use that term anymore?), I’d rather thank somebody personally with their

name, “Thanks Jamie” over “Thanks @slackuser21”. They’ll still see the gratitude

in their notifications unless they’ve deliberately left the conversation. If

they’ve deliberately left the conversation, then I see no reason to drag them

back in.

Once is often enough, if I’ve @-mentioned somebody, I usually wouldn’t do it

again for a while. I also pay attention to their working hours, and status

message before deploying the @. The Google Calendar app is great for

indicating to others when I’m in a meeting or not at work.

When Slack warns me “x is not in this channel”, I think carefully whether I

invite them, as prompted. I wouldn’t subscribe somebody to a newsletter without

their consent, so I prefer to send them a copy of the message and let them

choose for themselves whether they want to join. In Slack, “invite” seems to mean

“summon” and since I value context I try to share the context behind a message or

thread when sharing it to a channel where x hangs out.

# Reminders

These are a cool feature of Slack. Sometimes I read a message that I don’t have

the capacity to respond to at that time so I tell the sender I will come back to

them and I set a reminder for when I will get back to them. This works nicely.

# Deactivation

I mentioned earlier I’d deactivated some accounts. I like to manage folks’

expectations of me and I don’t want people sending me messages in Slack

workspaces that I’ll never revisit, expecting me to read or respond. Apparently

WhatsApp did not handle this well when I deleted my account (not just the app

from my phone). The URL for this is

https://<workspace-name>.slack.com/account/deactivate.

# Conclusion

🍫 You’ve read everything you need to.

Take a little break.

Now you can get things done!